†

ANTIQUES

Curio’s Practical Guide to Antiques:

Aubusson

Introducing Curio’s Practical Guide to Antiques, a place where we can immerse ourselves in the history of the world of antiques.

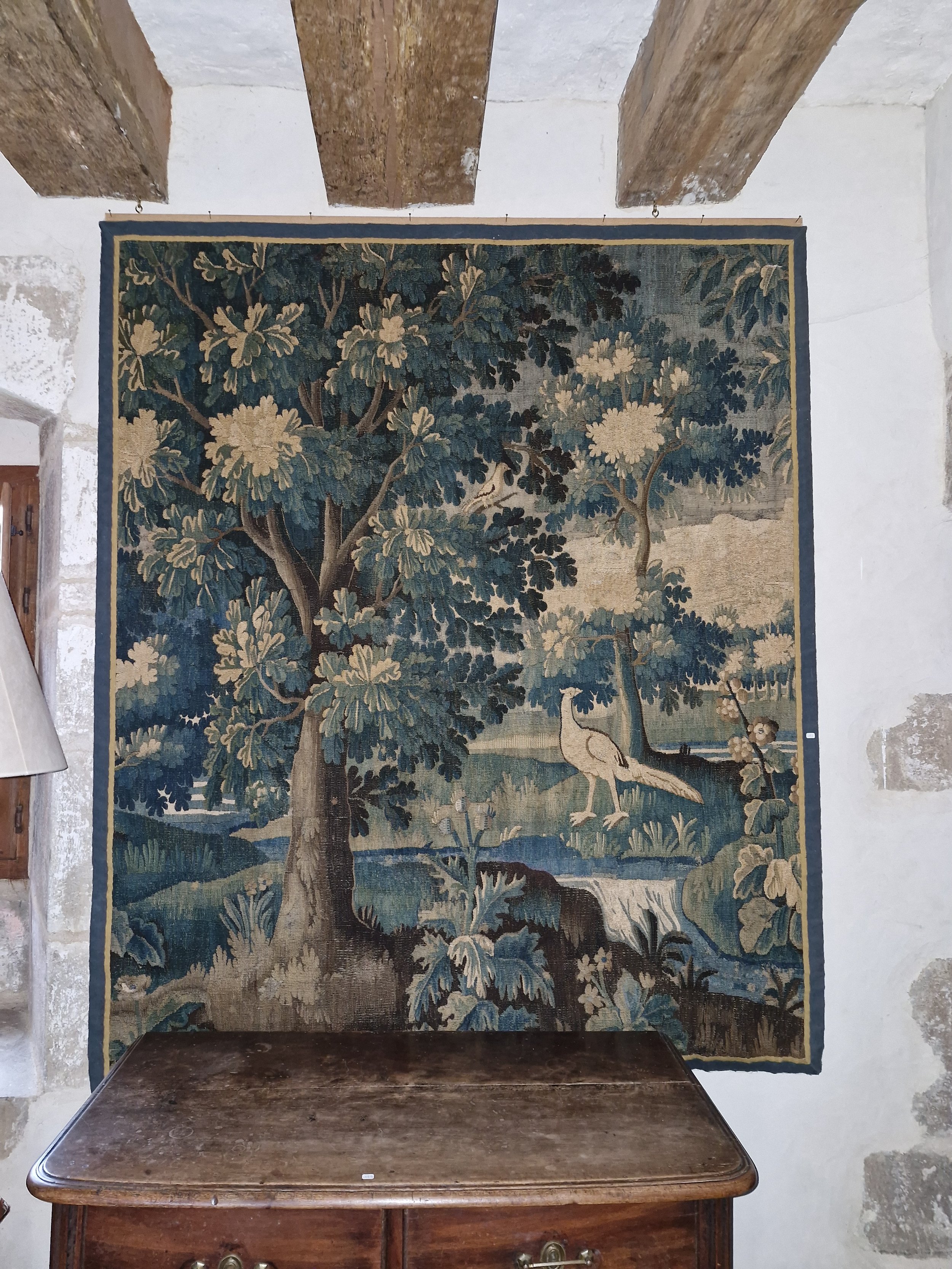

AUBUSSON, a small French commune located in the La Marche province at the base of the Creuse River, is a name synonymous with the production of fine tapestry, rugs, and carpets. According to local legend, some believe that the weaving trade was founded in the 8th century by Saracen soldiers following their defeat at the Battle of Tours. However, it is widely accepted by historians that the origins of its heritage as a textile center actually dates to the 14th century, when the town’s weaving trade began with small family workshops and guilds that prospered as highly skilled Flemish refugees came to Aubusson and set up looms. The acidic water of the Creuse River helped to degrease wool and setting dyes, making the town ideally situated for textile production. As tapestries of fine quality were extremely expensive to produce, Aubusson’s workshops produced textiles almost exclusively to a clientele of wealthy nobles, courtiers, and the church. Seen as status symbols, tapestries were considered to be a hallmark of wealth and prestige, with the large colored wall hangings adding insulation and gravitas to the halls of stately chateaus and drafty monasteries.

In 1665, the town was granted the official charter of “Manufacture Royale d'Aubusson” or “Royal Manufactory” by Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619 – 1683), First Minister of State to Louis XIV. Eager to boost the French tapestry industry at home and abroad, Colbert brought all French production of tapestries under his authority, issuing Royal Charters and setting specific standards for the workshops of Gobelins, Beauvais, and Aubusson. Each factory was given a distinct directive by Colbert. Gobelins was given the honor of making tapestries for the king and the royal family, Beauvais for France’s aristocracy and clergy, and Aubusson for wealthy merchants, courtiers, and for foreign export. While Beauvais and Gobelins specialized in mythological and religious scenes, Aubusson specialized in the production of the immensely popular verdure tapestries, or tapestries whose subject matter heavily features flowers and foliage. As weavers became more skilled, however, their creativity flourished and their verdure designs evolved to include pastoral or hunting scenes, with exotic birds, especially parrots, amongst the flora and glimpses of far-off castles or towns.

Detail of Antique Aubusson Watercolour tapestry cartoon c. 1870-1890, European Antiques

Part of what distinguished the chartered workshops of Aubusson, Gobelins, and Beauvais from the other, less skilled French workshops of the time was the utilization of a highly detailed production process that began with the creation of cartoons—to scale size models from which the tapestries were woven—painted in either oil on canvas or gouache on paper. Often, different painters would specialize in landscapes, flowers, animals or figurative subjects, and so several painters could have been employed on a single cartoon. The wools and silks were dyed to match the colors of the painting, which the weaver then copied.

As a result of Colbert’s support and these rigorous methods, some of the greatest French tapestries ever produced were made during the 17th and 18th centuries. At first, Colbert’s regulations specified a limited range of color dyes, called the Grand Teint dyes, chosen for their brightness and durability. However, in the 18th century, scientific advances in chemistry led to the introduction of new colors and, in the 19th century, the head of the dyestuffs laboratory at Gobelins, Michel-Eugene Chevreul, created a pallette containing 14,400 color-tones. By this time, as the British Antique Dealer’s Association (BADA) notes, “it is said that the Aubusson workshops could rival the work of the great Gobelins Manufactory in Paris, and the equally esteemed Beauvais factory. However, success was sharply curtailed in the late 18th century as Revolution swept through France.”

Cartoon painters at work at the turn-of-the-century, circa 1900

Weaving above a cartoon, on a low warp loom.

In the aftermath of the French Revolution, the workshops of Aubusson forfeited their protected status as Royal Manufacturers, and many workshops had to close as the weavers had lost their wealthy patrons to the guillotine. It wasn’t until Napoleon took a great interest in the textile industry, commissioning from Aubusson a series of floral carpets with the express purpose of reviving its business, that the once-great manufacturer was restored to its former glory. In more recent history, with the rise in popularity of wallpaper, which was far less costly to produce and to purchase, wall-hangings became less popular as interior decor. Nevertheless, the factories at Aubusson continued to prosper throughout the 19th century, although by this time they largely reproduced old designs and shifted much of their commercial output to rugs and upholstery coverings.

In 2009, the United Nations added Aubusson to its list of Cultural Heritage Sites in order to protect and preserve the art form and craft. Today the legacy of Aubusson tapestry endures, with three small businesses and approximately 10 freelance weavers using traditional techniques and operating in the area.

SHOP AUBUSSON TAPESTRY